|

|

Federal District Judge Charles Breyer issued a ruling in the California National Guard case earlier this week. He held that Trump may not federalize and deploy the Guard in California, nor send California troops to other states. Please note that while tonight’s column is a long one, I hope you’ll think it’s worth it. If you’ve lost the plot line in the California National Guard case, this should help.

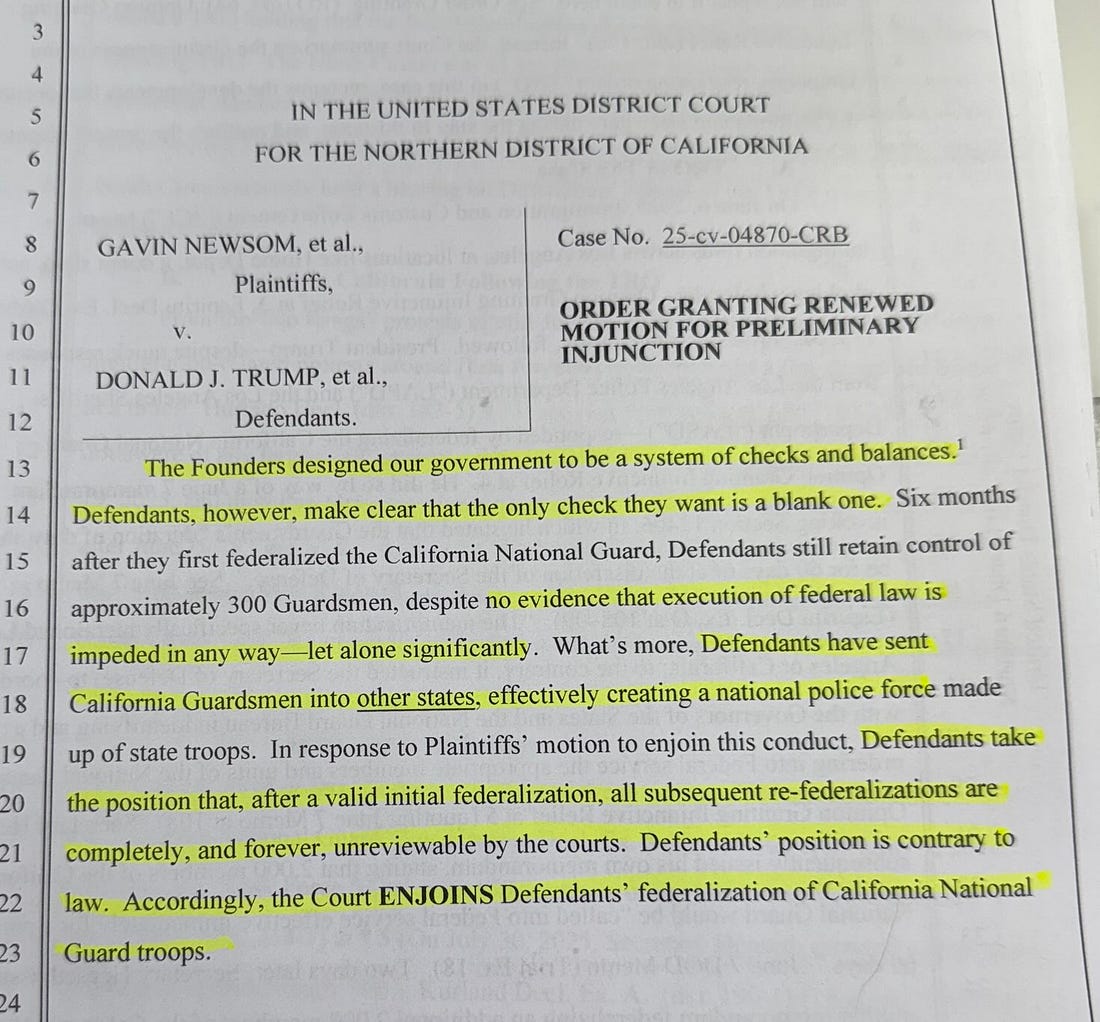

The opening sentence was stark: “The Founders designed our government to be a system of checks and balances. Defendants, however, make clear that the only check they want is a blank one.” The Judge pointed out that the government’s sole rationale for federalizing troops at the outset, the need for extra resources to enforce federal law, is no longer supported by any evidence (if, indeed, it ever was). And he equates Trump’s use of California Guard troops in other states with “creating a national police force.” But it’s his final point that may be the most hotly debated in the appeal to come: “Defendants take the position that, after a valid initial federalization, all subsequent re-federalizations are complete, and forever, unreviewable by the courts.” This is a position the administration has been pushing across the board in multiple contexts; once King Trump makes a decision, the courts can’t review it. That, of course, is contrary to the longstanding history and tradition of judicial review of the other two branches of government, which has been well-established virtually since the founding, as I discuss in detail in Chapter One of my book, Giving Up Is Unforgivable.

The Judge stayed his ruling from going into effect until Monday to give the government the opportunity to appeal, which it did on Thursday. That means the ruling is on hold until the Court of Appeals weighs in.

How we got to this point is, well, complicated. A little history of the case sheds light on why Judge Breyer entered this order at this particular time.

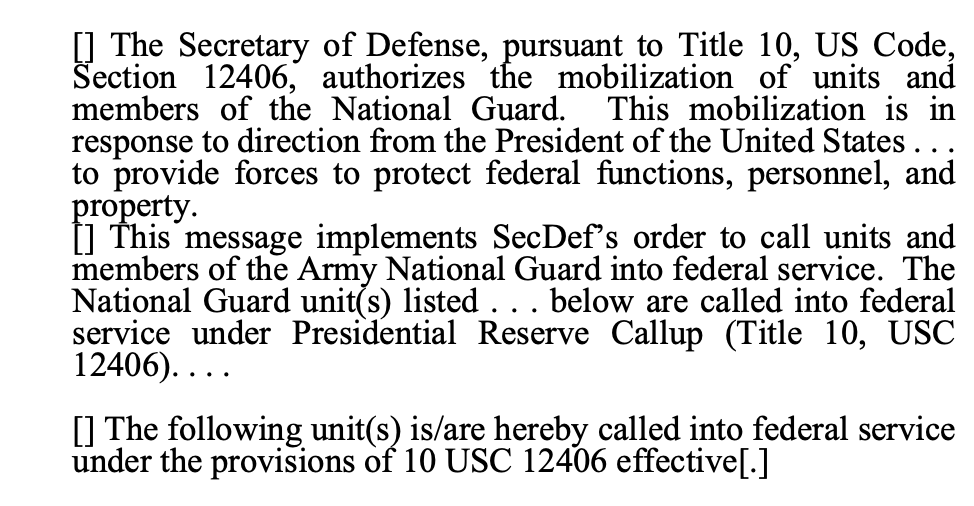

The core of the dispute involves 10 U.S.C. § 12406, the law Congress passed to give the president limited authority to exercise Congress’ own constitutional authority to deploy state militias (what we call the National Guard today) in specific instances. One of those, the one the government has maintained applies to Donald Trump’s federalization of National Guard troops in California and other states, is when the president “is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.”

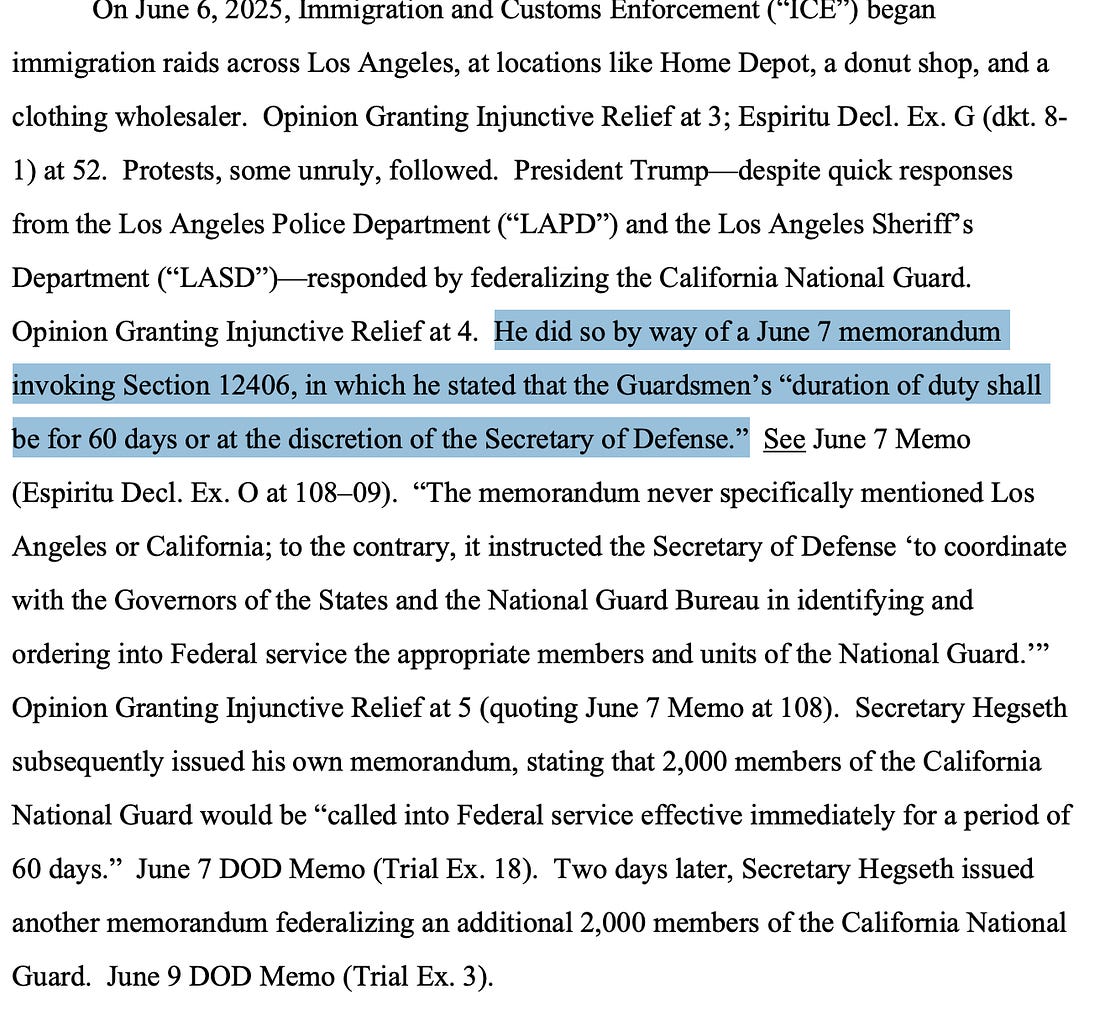

Trump’s initial federalization of California National Guard troops came in a June 7 memorandum invoking Section 12406. In it, Trump stated the Guard’s “duration of duty shall be for 60 days or at the discretion of the Secretary of Defense.” Federalized troops deployed the next day. And the following day, California Governor Gavin Newsom sued and asked the court for a temporary restraining order (TRO) to force the federal government to stop what it was doing.

This is the key to understanding the issues before the district court in the order Judge Breyer just issued is the timeline for what has happened in the case since it was filed. On June 12, this Court issued a TRO, preventing the government from federalizing troops while the court made an initial consideration of the issues. The government appealed the TRO to the Ninth Circuit, which paused it.

In doing so, the court articulated a very deferential standard of review to decisions made by the president. The panel held that courts won’t overrule a president’s decision to federalize National Guard troops as long as his determination “reflects a colorable assessment of the facts and law within a range of honest judgment.”

California asked the full Ninth Circuit to review the panel’s decision, in what’s called an en banc hearing, but on October 22, the court declined, permitting the panel’s decision stand. Senior Judge Martha Berzon, joined by 10 of her colleagues, wrote in a statement regarding the denial of rehearing that “The panel may have an opportunity to revisit its preliminary stance on the deference due the President, with the benefit of greater time and more extensive briefing, when it addresses the merits of the President’s appeal.” But for now, at least, that’s the standard that courts in the Ninth Circuit must apply to federalization orders under Section 12406.

This case is still in a very preliminary stage. There hasn’t been any decision on the merits in any court. The district judge issued a TRO, the sort of injunction that lasts for a brief period of time while a case is getting underway, and the government tried to keep it from going into effect by appealing. The Ninth Circuit has prevented Judge Breyer’s injunction from being enforced while it considers whether he was correct to keep the government from enforcing its federalization order while that appeal of the TRO was underway. Everything to this point has been an argument about whether the courts will preserve the status quo, with no federalized troops, while the litigation proceeds, or whether the government can federalize troops until the courts sort the issues out.

Of course, the courts don’t move quickly. Judge Breyer notes in his opinion that the Ninth Circuit has already held a hearing on whether he properly entered the stay, but as of Wednesday, had not yet ruled.

But while the Ninth Circuit works on its decision, more was happening in Los Angeles. Judge Breyer explains that the limited protests that erupted following the initial immigration enforcement actions and Trump’s deployment of the Guard petered out. Trump decreased the number of Guard troops that were federalized. Judge Breyer uses a statement released by DHS to explain what was happening in Los Angeles: “In mid-August, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem announced that the immigration enforcement mission had succeeded: the administration had ‘Removed the Worst of the Worst Illegal Aliens,’ arresting ‘4,481 illegal aliens in the Los Angeles area’ since June 6,” which demonstrates the diminished need for federalized troops. It sounded like the government thought things were getting better.

Then, on August 5, 2025, Trump inexplicably issued a new federalization order the day before the initial order was set to expire. He added 300 members of the California National Guard for 90 days.

On September 2, 2025, the California plaintiffs went back to the court, again asking for relief, this time in the form of a motion for a preliminary injunction against the additional deployment called for in the August 5 order. At the time, with the appeal to the Ninth Circuit underway, Judge Breyer wasn’t sure he had jurisdiction to act and declined to do anything. In the order he issued this week, he writes, “The Ninth Circuit later clarified that ‘Plaintiffs’ challenge to Secretary Hegseth’s August 5 order extending the California National Guard’s federalization through November 5 is not the subject of this appeal.’” That meant Judge Breyer was free to rule on the motion to keep the government from proceeding with the additional deployment called for in the August 5 order. The Judge invited California to update its motion so he could consider it, and the state added in an objection to a subsequent order the administration issued, an October 16 order federalizing 300 members of the California National Guard through February 2, 2026.

That’s incredibly complicated, picayune legal kind of stuff, but it’s essential to understanding what is and isn’t happening here. No court has said that Trump is A-okay to federalize troops under the statute. This is all about whether his actions will be stayed or not while the litigation is proceeding. Now, Judge Breyer is looking at this second deployment—which happened after the violence had died down and there was not even a colorable rationale for adding in more troops—and says to the government that it can’t do that while the litigation is underway and the courts are considering the merits of the issue here, which is whether the law affords a president the ability to do what Trump is trying to do here.

To obtai