| Can the ceasefire last? Is a further escalation truly avoidable? There are less than two weeks before a deadline that could lead to devastating reprisals. The conflict that has dominated attention this year is merely in abeyance. We’re speaking, of course, of the trade war initiated by President Donald Trump with his Liberation Day tariffs on April 2, and then put on a 90-day hiatus a week later. That pause ends July 8, and virtually no public progress has been made toward a resolution. Of more than 90 separate negotiations supposedly underway, none has yet come to fruition — other than a deal with the UK that changes almost nothing. And yet a combination of the tariff pauses (including a subsequent 90-day truce with China), the TACO trade (a belief that “Trump Always Chickens Out”), the failure of the levies to show up significantly in inflation, and the intense Iran crisis have pushed tariffs right down the agenda. This is a count of news stories published on the terminal, from all sources, so far this year: The risk that people haven’t been worrying enough about these developments can cause far more damage than those — like Iran — they’re watching obsessively. So is this degree of insouciance really justified? The pause only affected the wildly misnamed “reciprocal” tariffs, which reached as high as 44% on some unfortunate nations that run a big trade surplus with the US. The baseline 10% tariff on everyone remains in place. And that has had a massive impact on US finances. This is how monthly revenue from tariffs has moved since 2000: Various ultimatums along the way and a brief threat to levy 50% tariffs on the EU have produced virtually nothing. Trade negotiations are difficult, and Washington’s leverage isn’t as strong as it thought. To quote Macquarie’s Viktor Shvets: It seems that the US is relearning the Brexit lesson, when the UK believed that its persistent trade deficits vis-à-vis the EU gave it a powerful

negotiating lever, only to discover that relationships are symbiotic and

deficits by themselves do not explain much. While one could force much

weaker nations into a corner, it is harder with larger and more resilient

trading partners.

The chance of significant deals before the deadline is minimal. The US must also contend with the inconvenient truth that its trade deficit is chiefly driven more by its habit of spending a lot. The World Trade Organization, for all its faults, oversees a generally fair system with low tariffs all around. “Non-tariff” barriers either involve currencies — hard for governments to move — or policies deeply embedded in domestic politics, such as health and safety regulations. Beyond face-saving announcements that change nothing, little can happen before July 8. Markets are not, however, braced for the sudden reimposition of the crazily high Liberation Day levies. Instead, the new theory is that Trump has been “crazy like a fox” and will leave tariffs where they are. Using another animal metaphor, the world is a frog slowly boiling in water. The 10% tariff is the biggest new barrier to global trade since World War II, but people are getting used to it. At this point, if the US settles on “only” a 10% levy, the rest of the world (and global markets) would treat it as a victory. Critically, it’s not yet had any serious negative impact. Core goods inflation is ticking up and is now slightly positive — but it hasn’t taken off in any alarming way: Companies brought forward production to beat the levies, which may have delayed tariff effects — but S&P Global flash manufacturing PMIs for June, the third month in which 10% was in effect, suggest global industry is living with it without difficulty. PMIs across the developed world have risen since Liberation Day: Apollo Global’s chief economist Torsten Slok therefore argues that the president could extend the pause on reciprocal tariffs for another 12 months, and people would scarcely even notice the 10% barrier to their exports that remained in place: Extending the deadline one year would give countries and US domestic businesses time to adjust to the new world with permanently higher tariffs, and it would also result in an immediate decline in uncertainty, which would be positive for business planning, employment, and financial markets. This would seem like a victory for the world and yet would produce $400 billion of annual revenue for US taxpayers. Trade partners will be happy with only 10% tariffs and US tax revenue will go up. Maybe the administration has outsmarted all of us.

It’s also an elegant way for Trump to back away from a serious mistake without having to admit it. The bunker buster in Iran may have also busted any sense that Trump Always Chickens Out, making retreat on a signature policy politically easier. The US deficit adds impetus. Tariff revenue might help square a difficult circle as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act continues a tempestuous progress through Congress. Chris Wolfe of Pennington Partners puts it as follows: Tariffs are growth-dampening and socially corrosive — but surprisingly effective at raising revenue. So effective, they might cancel out the budget deficit created by tax cuts, but at the cost of low to even no growth.

On the same day that the Congressional Budget Office issued an estimate of an additional $2.4 trillion in debt, Wolfe points out that it also said that “the total revenue from tariffs enacted as of May 13 would reduce the debt by $2.5 trillion during the same period.” Earlier this year, there was a debate over whether Trump wanted tariffs to raise revenue, or as a lever for restoring US manufacturing jobs. He probably wanted both; there’s now a strong case to opt decisively for the former.  Manufacturing takes a back seat? Photographer: Justin Merriman/Bloomberg Any such approach would carry risks. Steven Blitz of TS Lombard argues that once a budget has been passed, in a process that may well require winning some Democratic votes in Congress, Trump will be able to amp up the pressure again: Once reconciliation is passed, Trump’s rhetoric on tariffs turns more aggressive. A lot of factors come to a head this summer. Muddling through is the default option the markets have voted for, understandably given recent history, but there are enough cross currents to suggest a more volatile outcome.

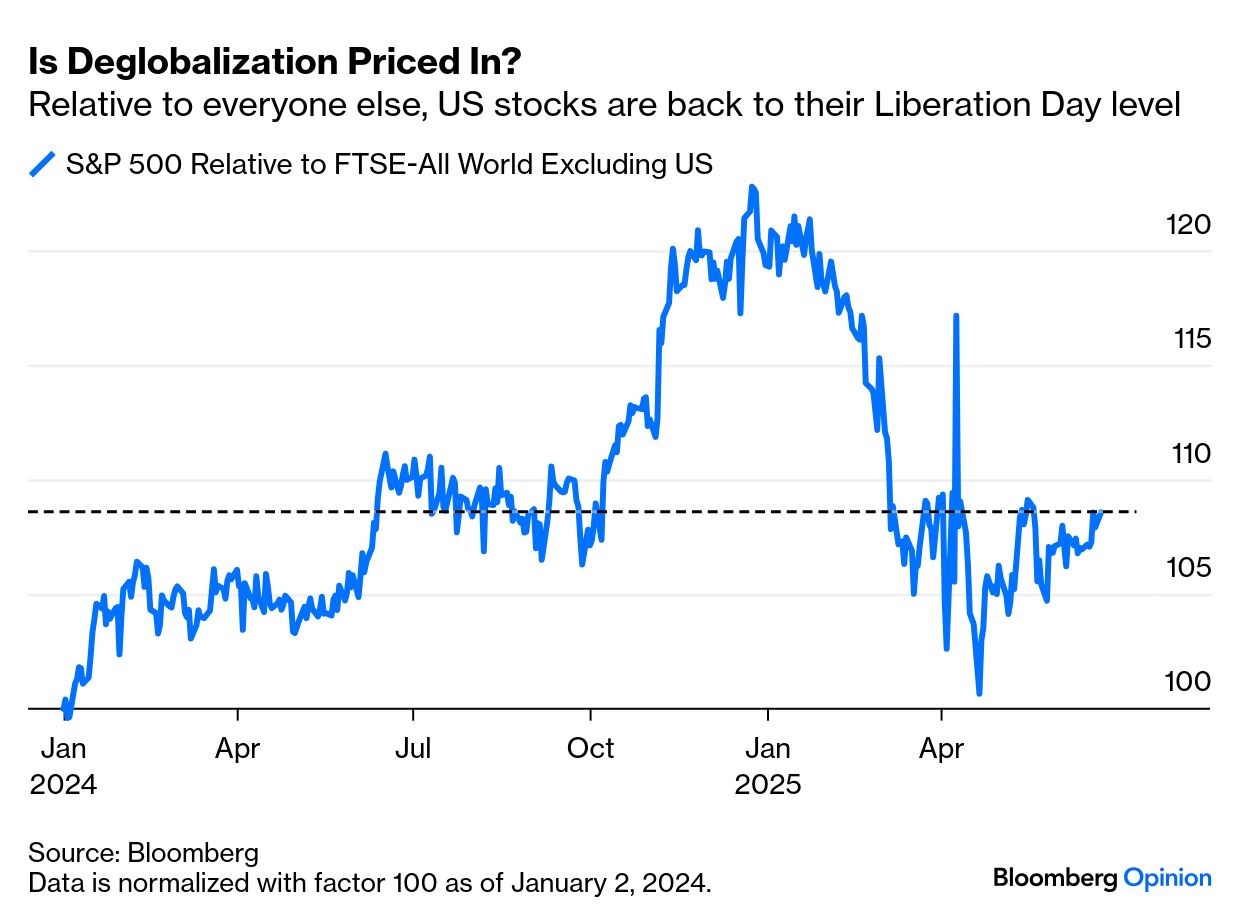

Iran does, after all, illustrate that Trump doesn’t always chicken out. And the last three months’ data have been noisy. Tariff inflation might yet show itself. That’s why the Federal Reserve is holding off cutting interest rates. As Chair Jerome Powell reiterated in Tuesday’s congressional testimony, tariffs’ effects will depend, in part, “on their ultimate level.” For now, he said the Fed was “well-positioned to wait to learn more about the likely course of the economy.” But a 12-month tariff pause would give everyone a chance to understand the effects of the 10% levy. As rising inflation would violate the president’s deal with his political base, it also offers a handy chance to retreat. Accepting a 10% baseline tariff also means going along with deglobalization, and acquiescing to a tax on the the profits of importing companies. The S&P 500 includes some of the greatest beneficiaries of the multi-decade trend now being rolled back. Globalization permitted them to cut back their cost of goods sold and widen their margins, as illustrated by this chart from Societe Generale SA’s Manish Kabra: A 10% baseline tariff will gnaw at that advantage. As it affects all imports to the US, America will inevitably hurt more than other countries, which will take a hit only to their trade with the US. And indeed, the S&P’s performance relative to the rest of the world shows a sharp correction earlier this year as traders grasped that Trump was serious about tariffs. It hasn’t been clawed back since Liberation Day and the subsequent truce, and if the 10% levy becomes a fixture, tightening margins could whittle away further at US exceptionalism:  Arguably, this forms part of the Trump base’s anti-corporate agenda. StoneX Financial’s Vincent Deluard argues that the administration is “redistributing income to workers” from companies. Trump’s 2018 tariffs on China didn’t dent margins, but Deluard says this was because the yuan depreciated, and China’s exports rerouted through Mexico, Vietnam, and India. This time, he argues that the onus will fall on corporate profits, and that the president’s political calculus needs this to happen: The 2025 tariffs will have a different impact because the dollar index has lost 10% this year, and tariffs are universal; therefore, importers cannot switch to non-tariffed suppliers. If foreigners don’t pay tariffs, their cost will be passed on to consumers or US corporate profits. The grand bargain of the Big, Beautiful Bill is to compensate for the tariffs’ inflationary shock with personal income tax cuts. If exchange rate adjustments, foreigners, and consumers do not pay for tariffs, corporate profits will.

If acquiescence in 10% tariffs does lie ahead, then the steady move out of US stocks has further to go. And there’s the fact that unlikely events can occasionally happen. Reimposing Liberation Day tariffs next month looks improbable — but a month ago, the same could have been said of a US attack on an Iranian nuclear facility. |