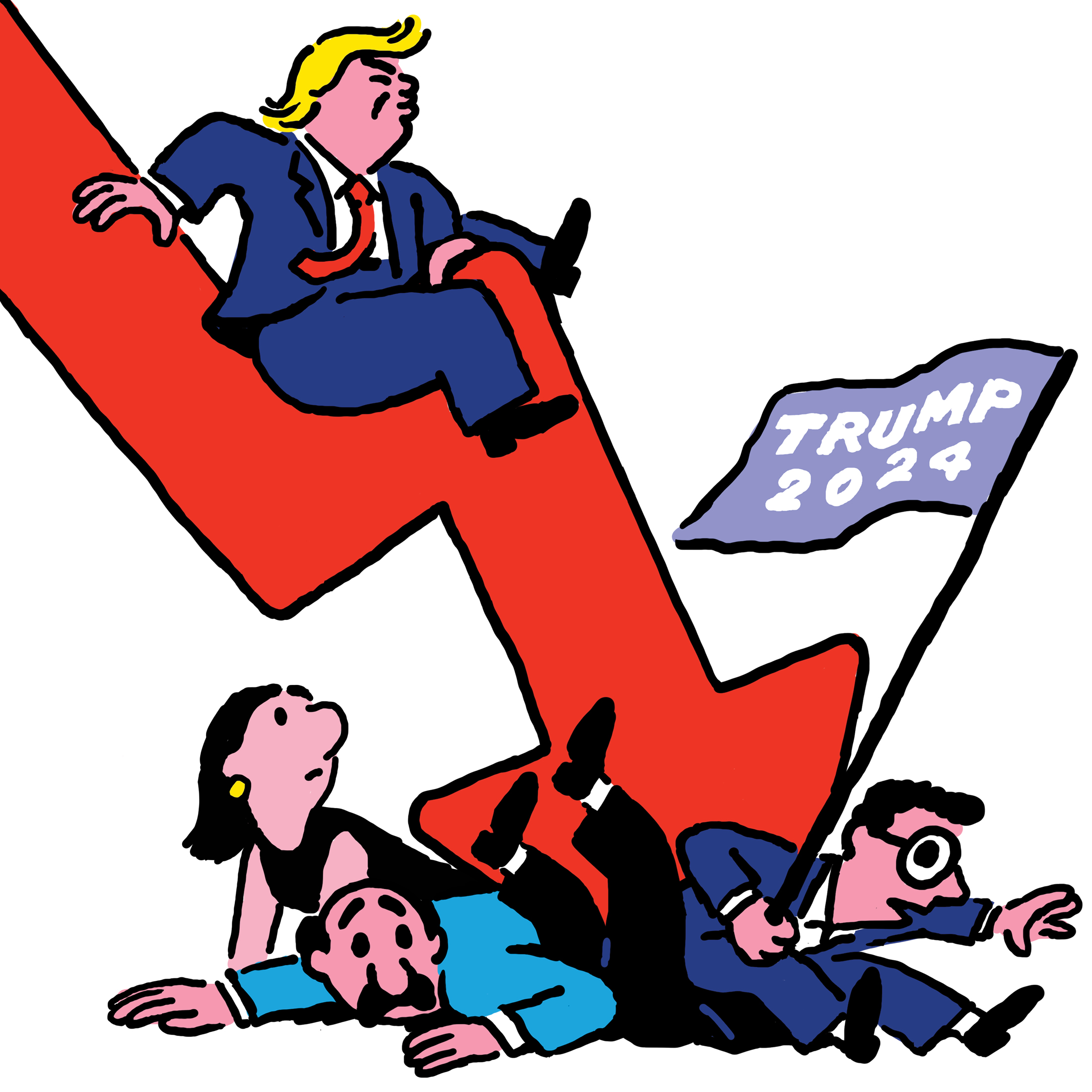

| Many of the chief executive officers who supported Donald Trump in the presidential election are losing their enthusiasm. In Remarks for the upcoming issue of Bloomberg Businessweek, Wes Kosova writes about the cost of the trade war so far. Plus: Selling exotic reptiles is a lucrative business. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. In April, as businesses across the US were starting to feel the weight of Donald Trump’s sudden, steep tariffs, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas asked Texas manufacturers to describe how things were going for their companies. The executives reported that factory activity had continued to rise and production showed modest growth. But the future was looking scary. “The tariff issue is a mess, and we are now starting to see vendors passing along increases, which we will have to in turn pass along to our customers,” a printing industry executive told the Dallas Fed. An electronics maker was just as blunt: “We have already had to turn around and refuse shipments, because customers cannot afford the tariffs, delaying our ability to build, which will eventually lead to job losses.” The Dallas Fed’s monthly Texas Manufacturing Outlook Survey is a widely followed barometer, because the state accounts for about 10% of US manufacturing—and because business owners there had enthusiastically embraced Trump, who won Texas by double digits in the 2024 election. Executives from 87 companies responded to the April survey, and overall they were a glum group. “Perceptions of broader business conditions continued to worsen notably,” the report found.  Illustration: Matija Medved for Bloomberg Businessweek A few months ago, American business leaders were largely cheering Trump’s return to the White House and his promises of explosive growth. “Starting on Day 1 we will end inflation and make America affordable again, to bring down the prices of all goods,” he said during the campaign. Postelection surveys of executives at companies large and small found business leaders preparing for what they believed would be an economic boom. Almost two-thirds of executives at midsize companies were optimistic about the prospects for the US economy in 2025, “an extraordinary shift in business sentiment,” according to a January report from JPMorgan Chase & Co. An influential monthly measure of CEO confidence from Chief Executive magazine also jumped after the election, with 82% expecting higher revenue in the coming year. By April that optimism had dried up, as Trump downplayed rising prices and instead announced punitive global tariffs that threaten to make just about everything Americans produce, buy or sell more expensive. Even if many CEOs were sitting silently or putting on a brave face in public, J.P. Morgan Research found “the uncertainty associated with tariff increases and the general thrust of the Trump administration’s policies are now depressing business sentiment, which will directly weigh on spending and hiring.” The Chief Executive confidence numbers deflated too, with 62% of CEOs in the survey saying they expected a slowdown or recession in the next six months. Frustration with the direction of the Trump economy is broadly felt. By the president’s 100th day in office, his approval rating in some polls had fallen below 40%, the lowest of any president at this point in his term in the past eight decades. “Basically, people voted for Donald Trump for four reasons,” says Republican pollster Whit Ayres. “To bring down inflation. To juice the economy. To stop illegal immigration. And to get away from ‘woke’ culture. The evidence on the first two suggests that increasing prices and slower growth are what’s being produced by the tariffs—which is exactly the opposite of why people voted for him.” If Trump is concerned that support for his economic policies might be crumbling, he isn’t letting it show. Instead, he’s pivoted in a way only Trump would do. The act of enduring rising prices from his tariffs has been recast as a patriotic duty. The picture he once painted of an instant golden age of America has given way to lectures on the virtue of rationing dolls for children—and, puzzlingly, pencils—as a way to force trading partners to come to the table on tariffs. “I’m just saying they don’t need to have 30 dolls,” Trump said in an NBC News interview in May. “They can have three.” That’s not likely to be a winning line, Ayres says, even if, as Trump points out, his supporters had to know he wanted tariffs. “Trump talked a lot about tariffs in the campaign, but people didn’t vote for an economic theory,” Ayres says. “People voted for an economic result.” Related: Trump Says 80% China Tariff ‘Seems Right,’ Ahead of Talks |